“This is not a community of fear!”—President Arbery’s Remarks at Matriculation 2021

Delivered on Sunday, August 23rd, at the formal Matriculation Ceremony that marked the opening of the 2021-2022 academic year

Freshmen, members of the Class of 2025, welcome back from an experience that already distinguishes you from your peers at other colleges. As I said to your parents last month, “One of the first experiences of our freshmen will be leaving behind the means of easy communication—the cell phone or the laptop—and encountering instead extraordinary landscapes that will become part of their memory and imagination for the rest of their lives.” You have formed deep bonds of friendship and mutual respect, and now that you have come back down from the mountains, you will read the books that have never ceased to form the mind of our civilization. What you have undergone will take you years to articulate. As the poet William Wordsworth wrote in his autobiographical poem, The Prelude,

There are in our existence spots of time,

There are in our existence spots of time,

That with distinct pre-eminence retain

A renovating virtue, whence–depressed

By false opinion and contentious thought,

Or aught of heavier or more deadly weight,

In trivial occupations, and the round

Of ordinary intercourse–our minds

Are nourished and invisibly repaired;

A virtue, by which pleasure is enhanced,

That penetrates, enables us to mount,

When high, more high, and lifts us up when fallen.

Throughout your life, in other words, memories from these weeks will come back to you to heal your mind and restore your spirits. This has been both a ritual of separation from the life you led before and a deepening of what you have always believed. It has been the beginning of your deep incorporation into the life and meaning of Wyoming Catholic College.

Part of that meaning is an understanding of heroism. When you enter the classroom this week, you will encounter in a new way those figures that the tradition of the West has always honored and whose names you have known since childhood: in Genesis, the patriarchs specially called by God; in the Iliad and the Odyssey, the heroes who explore the boundaries between the mortal and the immortal. These are men and women who step outside the common order into a uniquely charged sphere of unfolding meaning. They extend the expectations of mankind.

Part of that meaning is an understanding of heroism. When you enter the classroom this week, you will encounter in a new way those figures that the tradition of the West has always honored and whose names you have known since childhood: in Genesis, the patriarchs specially called by God; in the Iliad and the Odyssey, the heroes who explore the boundaries between the mortal and the immortal. These are men and women who step outside the common order into a uniquely charged sphere of unfolding meaning. They extend the expectations of mankind.

That does not mean that you will like them. Don’t expect Achilles to act like Aragorn or Captain America, for example, but give him his due and you might be afforded a glimpse into Homer’s grave and sublime exploration of the meaning of mortality, when even the most godlike of men must face the inevitability of death. When you see Abraham raise his knife over the bound and terrified Isaac on Mt. Moriah, you might reflect how profoundly such a moment goes against the grain of our wincing, politically correct times. Things would not go well for Abraham among the woke, I suspect. But these works have lasted through many different cultures and civilizations, and they remain vital in our own because they take us into the depths of who we are called to be in the real God-given world, not the technological simulacrum that we invent for what Thomas Hobbes calls “commodious living” and then populate with our touchy sensitivities.

Heroes and saints are not necessarily easy to get along with, since they answer a higher call that puts them at odds with the world around them, even those closest by. It is not easy to fit the hero into ordinary life, but without these primordial figures, we would not hope for more in human life than good internet service and enough coffee—not that I mind these things, just for the record. But here at Wyoming Catholic College, we have a culture of expectation that calls at every point upon the best that is within you. This is not an education geared to trigger warnings and safe spaces, but to courage and prudence and justice and temperance—and of course, beyond those, to the holy gifts of faith, hope, and love. We are not engaged in tearing down or demeaning what is great, but in honoring whatever is noble and good, wherever it might be found. I was reading yesterday about Winston Churchill’s refusal to speak badly those of other races and cultures merely because they were the enemies of Britain. As this writer puts it, “Churchill always regarded the enemy as human beings capable of displaying courage and heroism…. Here one breathes the humanizing ‘spirit of magnanimity tied to moderation, restraint, and mercy.’”

Heroes and saints are not necessarily easy to get along with, since they answer a higher call that puts them at odds with the world around them, even those closest by. It is not easy to fit the hero into ordinary life, but without these primordial figures, we would not hope for more in human life than good internet service and enough coffee—not that I mind these things, just for the record. But here at Wyoming Catholic College, we have a culture of expectation that calls at every point upon the best that is within you. This is not an education geared to trigger warnings and safe spaces, but to courage and prudence and justice and temperance—and of course, beyond those, to the holy gifts of faith, hope, and love. We are not engaged in tearing down or demeaning what is great, but in honoring whatever is noble and good, wherever it might be found. I was reading yesterday about Winston Churchill’s refusal to speak badly those of other races and cultures merely because they were the enemies of Britain. As this writer puts it, “Churchill always regarded the enemy as human beings capable of displaying courage and heroism…. Here one breathes the humanizing ‘spirit of magnanimity tied to moderation, restraint, and mercy.’”

This is not a community of fear, eager to comply with whatever is proposed as good in the culture at large. By our very existence, we stand in opposition to many figures and trends in contemporary society, but what we oppose, let us oppose nobly, always open to what is best in those who consider us wrong. Surely that charity follows from loving our enemies. I very much hope that we are a community disciplined, not by fear of the federal government but by the fear of God. What does that mean? You freshmen had many occasions of learning good fear these past few weeks. Fear of God does not mean backing away from danger any more than you would back away from the challenge of a peak ascent. In moral choices, it does not mean a cowering and self-obsessed scrupulosity, but a responsible self-respect grounded in God’s love for you in the situations you face daily. It means respect for others and attentiveness to the possibilities for justice and for mercy. Fear of God, in the sense that I mean it, is awareness of another choice when there is a temptation to sarcasm or laziness or self-indulgence. Moment to moment, there is a better way, a best way. Fear of God means a dread of choosing what you know to be wrong or of letting some harmful thing happen through weakness or indifference or inattention.

It is possible that obvious moral choice might not be involved at all. Suppose you are writing a paper, and you know that you have not yet said exactly what you intuited. What is it, exactly, that urges you to make the extra effort, even if you have written something that might get by? It’s not fear of a bad grade, but fear in the sense of respect for the truth, respect for the real existence of the best and the most beautiful. Fear of the Lord is wholesome and cleansing, like cold mountain air. It is the kind of fear that makes you alert and urges you pay attention and watch where you are going because when you do so, you know Him. He is attention and presence itself. Proverbs 9:10 says that “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom,/ and the knowledge of the Holy One is insight.” In this community, may holy fear guide us into the courage we need, and may it bind us to the right.

It is possible that obvious moral choice might not be involved at all. Suppose you are writing a paper, and you know that you have not yet said exactly what you intuited. What is it, exactly, that urges you to make the extra effort, even if you have written something that might get by? It’s not fear of a bad grade, but fear in the sense of respect for the truth, respect for the real existence of the best and the most beautiful. Fear of the Lord is wholesome and cleansing, like cold mountain air. It is the kind of fear that makes you alert and urges you pay attention and watch where you are going because when you do so, you know Him. He is attention and presence itself. Proverbs 9:10 says that “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom,/ and the knowledge of the Holy One is insight.” In this community, may holy fear guide us into the courage we need, and may it bind us to the right.

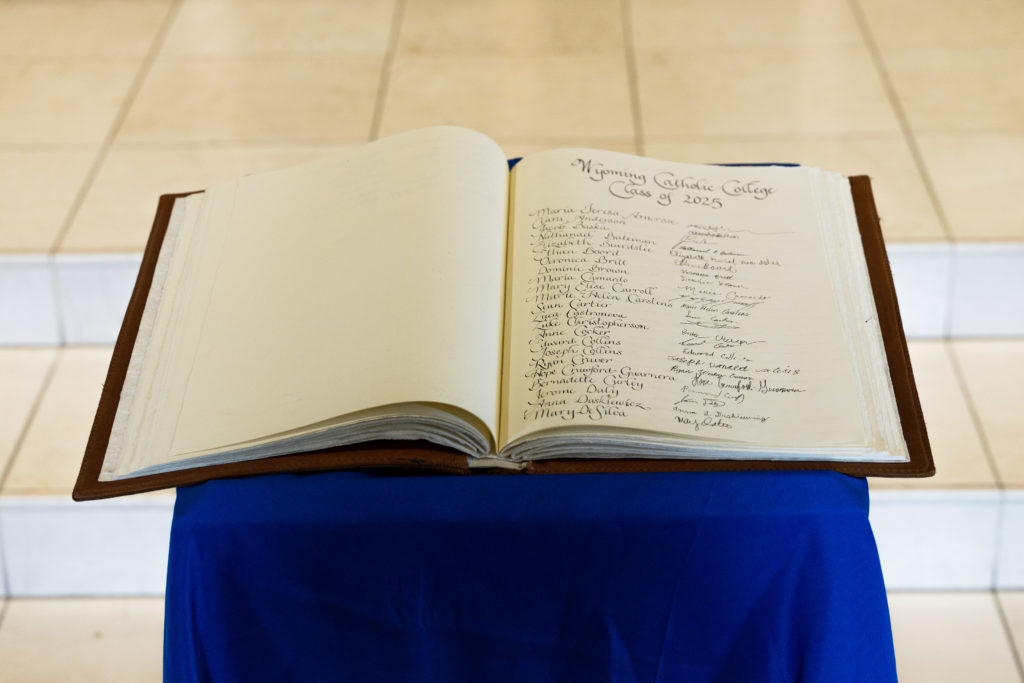

As you begin your life as a student, I urge you to keep in mind the heroism to which you are called. You have already faced one set of challenges, and now you face a different kind, perhaps even more demanding. What you learn will form your life and reward you with great abundance to the extent that you pursue it with a whole heart and a whole mind. In just a moment you will come up to sign the book that contains all the names of all the students who have ever matriculated at Wyoming Catholic College. On behalf of this growing community, which you enter as you sign your name, please accept my heartfelt welcome.